Based on a lecture to the Helensville Historical Society by Margaret Kawharu

(Trustee, Ngā Maunga Whakahii o Kaipara)

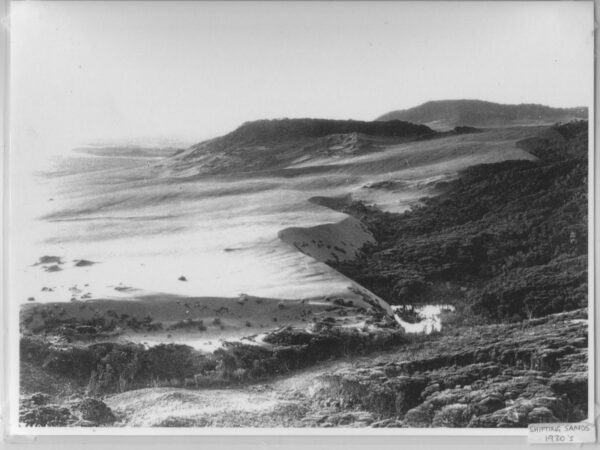

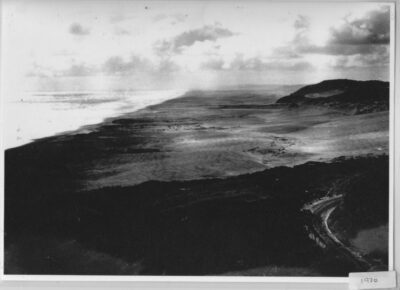

This historical account of the Woodhill area begins at a point in time mid way shall we say, in our shared history of Māori and European settlement around Woodhill. That would be around 1900. Sand encroachment on to farmlands from the west coast had been a problem in the Kaipara region since the early 1900s. There had been piecemeal attempts to arrest the encroachment through planting marram grasses and lupins. From April 1920 work began planting marram grass plantations on farmers’ land and was overseen by Samuel Stafford. The workers were mainly Māori from Reweti including Joe Hoterene and driven by the personal enthusiasm of the Commissioner for Crown Lands, Reginald Greville. After Greville’s death in Sept. 1923, much of the momentum dissipated. [Goldstone p.37-39]

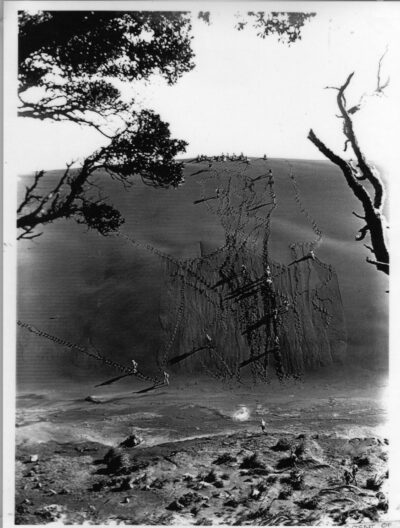

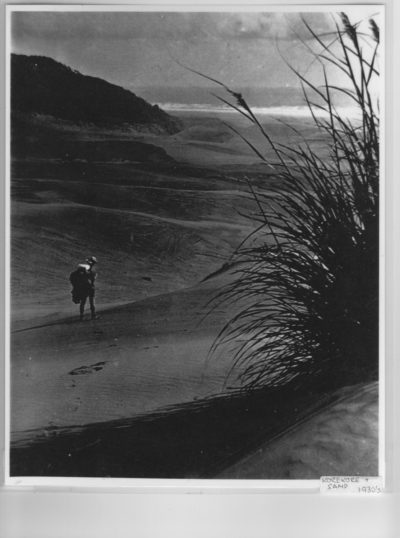

The Public Works Department noted that in places the wall of sand was over one hundred feet high and the drift could advance as much as forty feet in one westerly blow. Repeated fires for the purpose of providing pasture, driving out the wild pigs and deer, very soon resulted in exposing the underlying sand and setting wide areas in motion [Director of Forestry 1924, Alexander p.289]. Fire and wind were not the only things which caused the sand to advance but also cattle, sheep and rabbits would start the sand moving. Heavy rains then washed the sand down and exacerbated the silting up of the Kaipara River and threatened to turn the fertile flats into swamp. [Alexander p.312-3].

Lobbying from European land owners concerned about the spread of the sand-drift on to good farming land prompted efforts to make a more coherent policy around the sand dune reclamation programme. In 1925 it was decided that the responsibility for the sand dune reclamation would be with the State Forest Service although the service was unwilling as they deemed reclamation to be an uneconomical venture.

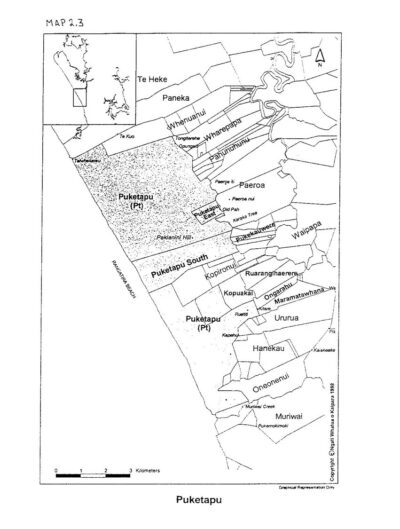

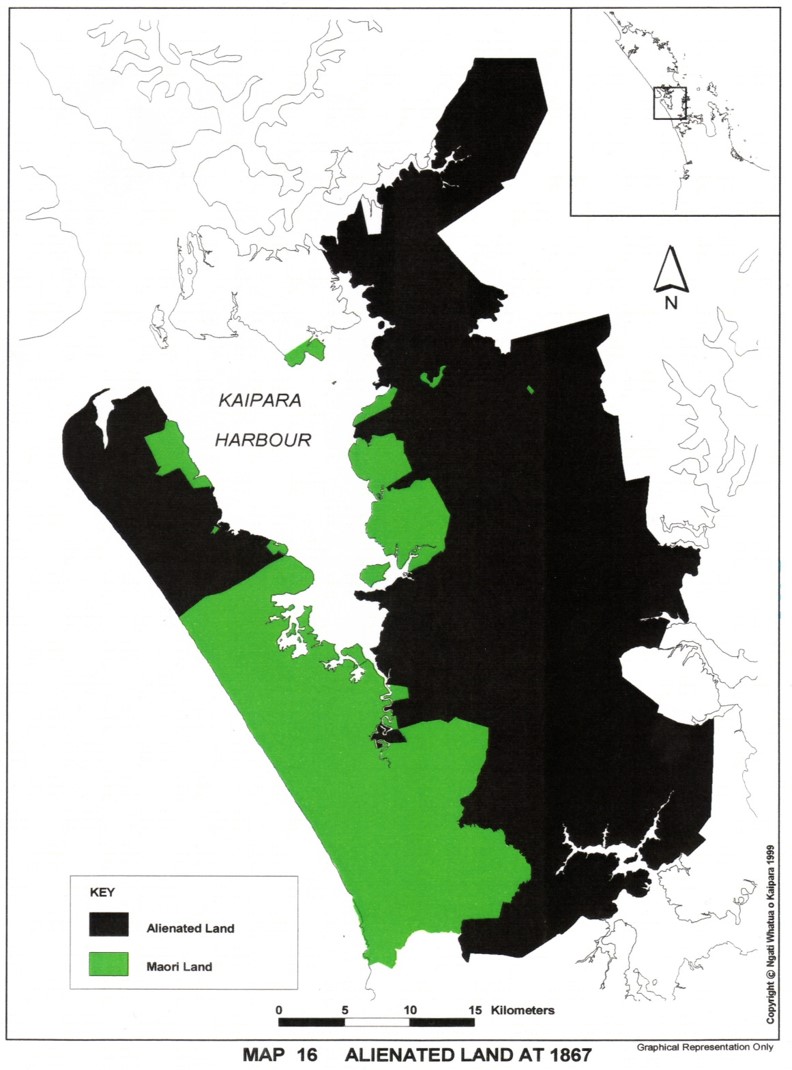

By 1921 the southern Kaipara peninsula contained a sand area of approx. 31,270 acres southwards from South Kaipara Head. The Crown already owned 15,790 acres from purchases made in the nineteenth century. Around 2500 acres was private freehold land and 12,980 acres was Māori customary land. The most severe drift was from the Ngāti Whātua owned land generally known as Puketapu, and two adjacent blocks, Puketapu South and Whenuanui, as well as Pukemokimoki, Kopironui, Hanekau, Te Keti and Ururua. State officials argued that it was imperative for the Crown to obtain title as soon as possible.

As Puketapu was still customary land the title was investigated in 1921. Title to 7325 acres was awarded to 89 owners and 75 acres in 4 burial grounds (urupā) were awarded to 8 trustees. Then the Crown focused on purchasing individual interests. In order to facilitate sale, the Crown imposed restrictions from July 1927 to 1931 upon the block, prohibiting any alienation except to itself under Section 363 of the Native Land Act 1909. There was no requirement to consult the owners who were prevented from alienating their land, except to the Crown. Thus many owners were left with little choice but to sell. Between 1925 and 1931 almost all of the interests in Puketapu (151 shares out of 156 in total) were sold to the Crown but the remaining owners were adamant in their refusal to sell. They wished for their outstanding interests to represent areas located alongside or adjoining their four urupā.

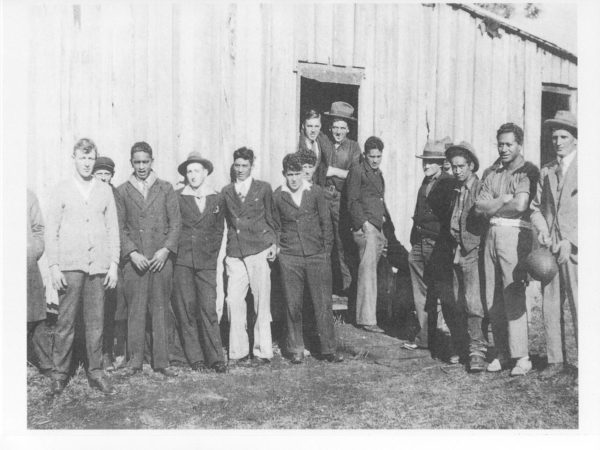

By 1931 the member for Kaipara, Gordon Coates was appointed Minister of Public Works and Employment in the new coalition Government. He came under pressure from local organizations for something to be done both about the sand dune problem and unemployment [Goldstone p.50]. Thus the sand dune reclamation programme became an initiative of the Public Works Department as an unemployment relief scheme. Until the outbreak of war, approx. 100 married men were provided with relief work each winter and half that number over summer for marram planting. Some Māori like Bill Tangaroa did find work on the sand hills from 1932 onwards using their European names to get work.

The Crown wanted full and permanent control of the land under sand dune reclamation because it was thought that if land was to revert to private commercial use the sand drift problem would re-emerge. Most European farmers were willing to hand over the land affected to the Crown and a number of them actively sought to get rid of what was to them a liability rather than an asset. Many freely provided horses, accommodation and gardens for relief workers [Goldstone p 60-61]. Between 1932 and 1936 agreements were struck for title to the farmers’ sand country plus half a chain in. The amounts of land involved varied from 13 perches to 1623 acres. The purchase price in all cases was a nominal one shilling regardless of area. In total more than 5960 acres of privately owned land was acquired for less than £3.

In June 1934 a Gazette notice advised of the Crown’s intention to take the parts of Puketapu it had purchased and other blocks for sand dune reclamation under the provisions of the Public Works Act 1928. The notice also listed the 4 urupā. The notice advised that plans were available for inspection at the Woodhill Post Office. There is doubt that the remaining owners received a ‘notice of intention’. Eight of the owners in the seven other Ngāti Whātua blocks which were going to be taken, were served notices in August 1934. Five European landowners also received notice of the intention to compulsorily take all or part of their land, part of Hanekau, Maroroa, Paengatohorā and Taupaki. Yet there is no record of any of the remaining owners of the Puketapu blocks being officially notified. Puketapu was compulsorily aquired from October 1934. Notably as soon as the owners were aware that their land was being taken, Hariata Whareiti and sixteen others petitioned Parliament in November 1934 requesting that their interests be protected particularly with respect to the urupā [Small, p.164-6]. Because the 4 urupā had been vested in the Crown under section 11 of the Reserves and Other Lands Disposal Act 1934, the Crown was enabled to take the urupā for sand dune reclamation purposes subject to the owners retaining their burial rights [Small p.173]. No further action was taken until after the compensation hearing in May 1935.

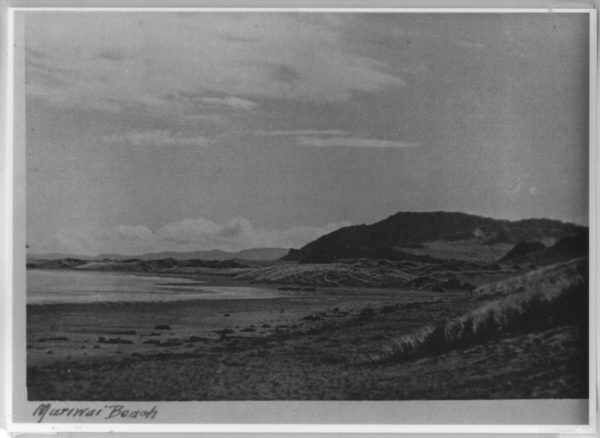

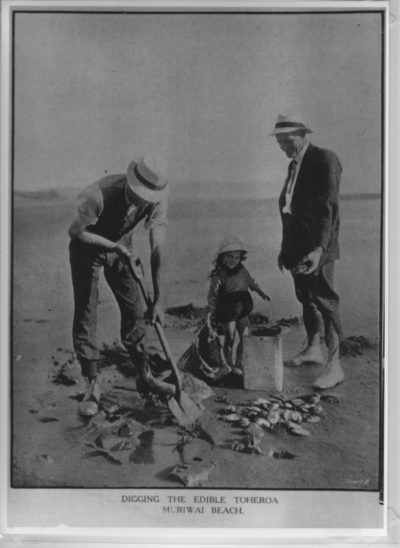

The central issue at the Native Land Court compensation hearing was clearly access, both to the urupā and to the beach. Lack of prior consultation was a major problem for the remaining owners, and also the fact that there was no provision to appeal against Public Works takings. The Public Works Dept. were adamant access across the sand dunes would have to be controlled. The Dept. admitted the importance of kaimoana to Ngāti Whātua, especially in the winter, but argued they would still be able to access the beach by road. Comparison was made between the European owners having given over land to the Crown without thought of claiming compensation.

But one Maori owner, Pakiorehua Uruamo, stressed the importance of access to the beach, saying, “All the people in my house live on toheroas and fish, and kumera during the winter. We cannot milk during the winter. We depend on the beach for our living.” She went on to say, “I ask for no compensation. I object to the taking of the land. … I will not take compensation even if the Court awards it to me. The money can be used for reburying our dead.” [Small p.169; Goldstone, p.74]. Hariata Whareiti opposed the taking of the urupā out of fear that “Perhaps Pakeha will tamper with our burial grounds and take greenstone relics.” The Crown representative at the hearing undertook to allow access to the urupā and to act to prevent further damage to these sites.

Judge Acheson pointed out the Crown’s failings stating that, “The Court would have much preferred the Government officials to have gone to the extreme trouble to provide at least one access route to the beach for food supplies.” Acheson also stated that it was up to the Crown, not the Court, to assess compensation for the loss of access rights to Ngāti Whātua. “The Court cannot understand responsible Government officials maintaining by argument or definite statement that the deprivation of access to the beach is not a serious hardship and a big financial loss to the Natives.” As Acheson assumed that Ngāti Whātua would either petition Parliament or appeal against the Court, he drew attention to the Crown’s obligations under the Treaty of Waitangi which “guaranteed to Natives the rights to fisheries.”

In his summary, Acheson also commented that the Natives were not objecting “for the purpose of squeezing out a big sum of compensation but have a genuine need for the access and will suffer real hardship by its loss. Very few if any of them will benefit by the reclamation. The European affected will benefit greatly.” [10/5/1935: KMB 19/365-366, Small p. 171]

Ngāti Whātua from Reweti duly petitioned Michael Savage, the new Labour Prime Minister, in December 1935, over the loss of access to kaimoana. They were supported by a local resident Mr Moore. A year later another petition was sent from the local Māori Labour Committee demanding formal access. The response of the Government was the same – that tracks would result in sand blow outs and run the risk of fire. Access was not provided, and no compensation for the loss of access was ever assessed. In the event of a burial, Public Works officials were to grant permission.

Acheson awarded compensation for the Puketapu blocks and Whenuanui at the same level as the prices received by the other owners between 1921 and 1930. Another hearing was held in January 1945 with respect to parts of Kopironui and Pukemokimoki and compensation forwarded to the Tokerau Maori Land Board in May 1946. More land was acquired after the war including Kopironui B2D2, which now forms the main access into Woodhill.

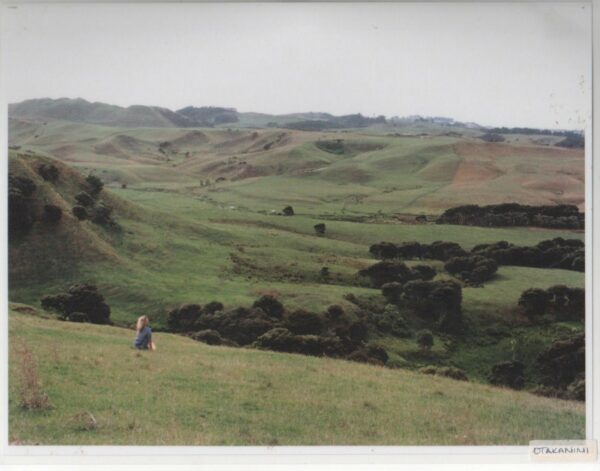

From 1936 the Public Works Dept. began planting pinus radiata as the final phase of stabilization. The lands taken for sand dune reclamation were declared Crown land in February 1957. In May 1959 Woodhill was set aside as Permanent State Forest. Attention had turned to the South Kaipara Head area north of the Ōtakanini Block to enable the stabilization of a continuous belt. Agreements had been entered into with owners of parts of the Aotea and Paparoa blocks earlier in 1948, so they were reactivated and the land sold to the Crown.

The RNZAF had indicated their wish to use a portion of the reclaimed area for a bombing practice range.

The owners of the Ōtakanini block were in the process of establishing an incorporation and the Crown met with a small liaison committee early in 1958 to broach the idea of purchase of the sand dunes by the Crown. But the committee decided against the sale of the land and eventually entered into a 99 year lease to the Crown instead in 1969.

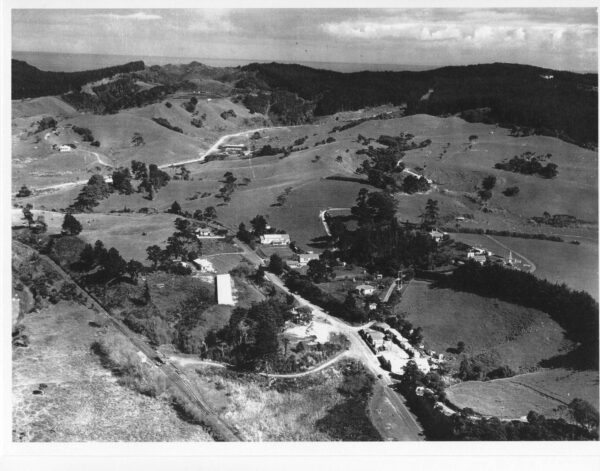

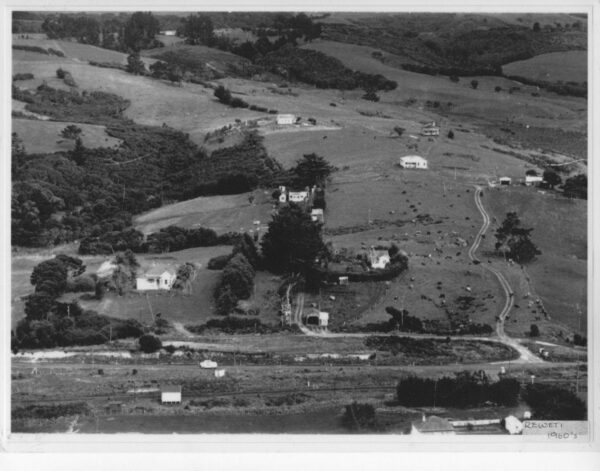

From the 1950s the Forest Service took a more common sense approach to the issue of access and the public were allowed access to the forest as long as they had permission from the HQ first. The Forest Service had a strong ethos of community and public service particularly at Woodhill under Allan Restall. Locals were allowed into the forest at weekends to collect firewood, and lupin seed. In 1970, at the initiative of Bill Drower, public access was allowed between Rimmers Road and Muriwai Beach. The Forest Service supplied water, toilets, carparks and fireplaces. An estimated 8000 people used the road on 2 weekends during the 1970 toheroa season and people continued to be allowed into the forest for fishing, birdwatching and other pursuits such as trail biking and 4 wheel driving. From that time managed public recreational activity was facilitated in the forest.

One particular problem group at Woodhill was hunters. Deer hunters poaching in the area tended to establish camps and light fires in the marram and lupin, as well as trespass upon private farms. Prosecutions for trespass began in 1952 and continued into the 1970s. From the 1980s cannabis growers, whose plantations within the forest were a danger to forestry workers and the general public, were also prosecuted.

In September 1985 the Government announced its intention to restructure the Forest Service. In line with other State Owned Enterprises, forestry would operate with clear profit-making objectives. According to Forest Service staff at Woodhill, the entire workforce of about 50 staff and workers, with the exception of a few senior staff, were made redundant. One long-serving worker described it as an “absolute disaster” for the forestry community that had grown up at Woodhill, especially as many of the workers had spent most of their working lives in the forest. Restructuring came at a very heavy price for the local people. Timberlands took over in 1987.

For the local Māori people it was a particularly bitter pill to swallow. According to them, when it was first proposed that the Crown take ownership of the lands for the sand dune reclamation, the benefits in return would be opportunities for employment on the railways, planting marram grass and eventually in the forest that would be established. Bill Tangaroa and Kelly Povey and others from Reweti were so employed and in accepting employment they were able to protect the sites of significance. But corporatisation meant redundancy for many people as well as for Māori being disconnected from and unable to monitor forestry operations with regard to wāhi tapu.

The famous Lands Case that went to the Court of Appeal in 1987 included Woodhill as one of the case studies presented by Te Kahui-iti Morehu, Hugh Kawharu and archaeologist Ian Lawlor. It was argued that the Crown had no right to sell its land assets out of Crown ownership where issues between Māori and the Crown were still unresolved. The Court of Appeal upheld the decision that Crown lands which could potentially be used to redress such grievances could not be sold in the meantime. So in 1988 the Government decided to sell its forestry assets. In July 1990 the crop on Woodhill was valued at $45 million. The license to Woodhill Forest was sold to Carter Holt Harvey later that year. The Court of Appeal case was the impetus for a Treaty claim to be lodged with the Waitangi Tribunal in 1992.

It is at this point that our story takes another turn. In 1989 the Crown Forest Assets Act identified the need for research into the Crown’s acquisition of its forest lands and made available funding from the interest on the rentals it received from lessees like Carter Holt Harvey for that purpose. Ngāti Whātua was protesting against Western Illmenite’s proposal to mine the black sands along Muriwai Beach when the Crown Forest Manager, Cecil Hood, made the Crown Forest Assets Act known to them as well as the Crown Forestry Rental Trust. A funding application was duly made to the Crown Forestry Rental Trust for the management and research necessary to present a claim to the Waitangi Tribunal. By that time an important distinction had been made, which was that the claim should not only be focused on the forest lands but should recognize the forest land and its former owners in context, from 1840, the point from which the Waitangi Tribunal now had the jurisdiction to make its inquiry into land claims arising out of breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi. The Treaty of Waitangi obliges the Crown not only to recognize Māori interests, but to actively protect them.

I’d like to take this opportunity to give a brief overview of the claim because it is important to understand that from the beginning, the return of Woodhill Forest land to Māori ownership has been central to remedying the land claim, the details of which are set out in various pieces of legislation and negotiations with the Crown.

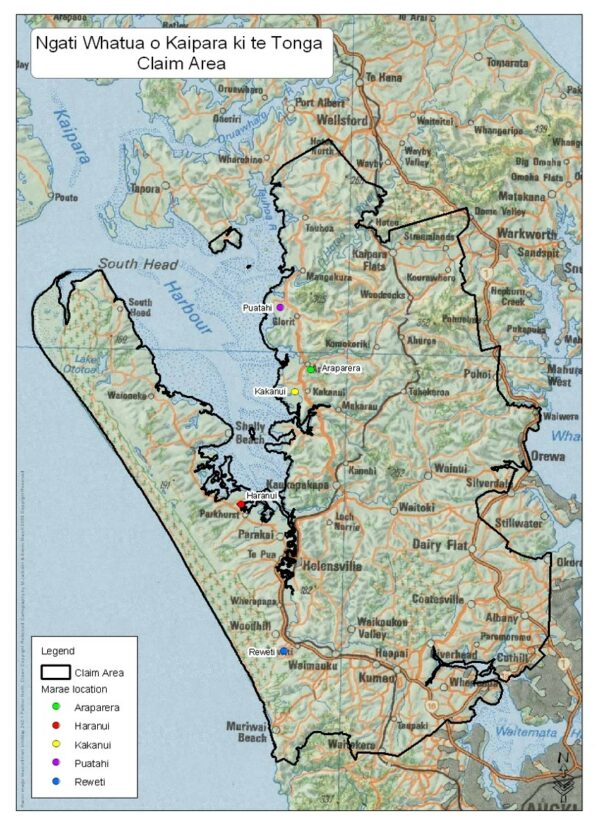

The South Kaipara claim is summarised as being one made by Takutai Wikiriwhi and others on behalf of the whānau and hapū of Reweti, Haranui, Araparera, Puatahi, and Kakanui Marae. It is a comprehensive claim covering the loss of Ngāti Whātua lands in southern Kaipara through old land claims, pre-emption waiver claims, Crown purchases, the operations of the Native Land Court, and public works takings. Other grievances related to the gifting of a 10-acre block at Te Awaroa (Helensville) and land for the Auckland to Te Awaroa railway, and to aspects of the sand-dune reclamation works at what became Woodhill Forest. A distinctive feature of South Kaipara is the claim that Ngāti Whātua had an ‘alliance’ with the Crown. It is claimed that this alliance placed particular obligations on the Crown that were not met. Two overarching themes in the South Kaipara claim are the Crown’s alleged failure actively to protect Ngāti Whātua’s land base and the allegation that the Crown made promises of economic development and the provision of services to Ngāti Whātua which it failed to fulfill.

![alienated-land-1900[1] alienated-land-1900[1]-Woodhill Forest-Ngāti-Whātua-o-Kaipara-film-tv-production location-events-equestrian access-horse park-Woodhill Forest-Ngāti-Whātua-o-Kaipara-film-tv-production location-events-equestrian access-horse park](https://www.woodhillforest.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/alienated-land-19001-woodhill-forest-ngati-whatua-o-kaipara-film-tv-production-location-events-equestrian-access-horse-park-woodhill-forest-ngati-whatua-o-kaipara-film-tv-production-location-events-equestrian-access-horse-park.jpg)

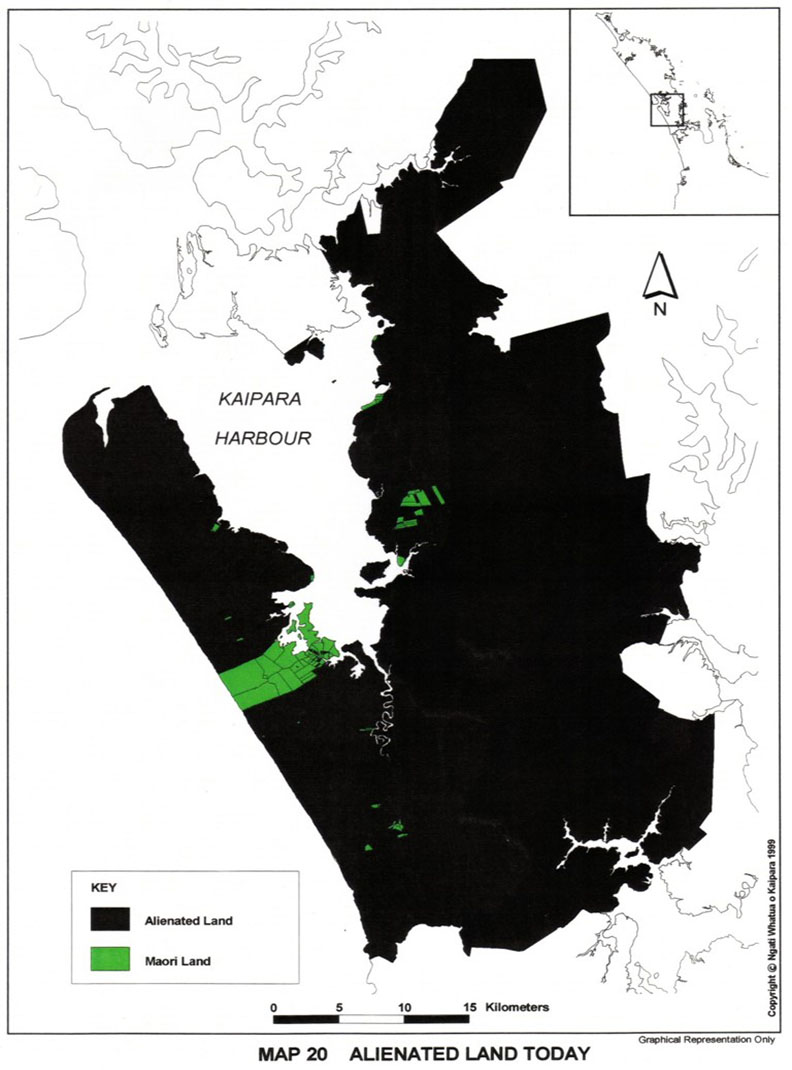

The Waitangi Tribunal in its Kaipara Report issued in 2006 found that, “The legacy to Ngati Whatua of over 150 years of Pakeha settlement in southern Kaipara is a number of small Maori communities struggling to survive on remnant scraps of land with limited resources. Many families are living in poverty, with low levels of educational attainment, poor health status, and few economic opportunities. The Crown must take some responsibility for this state of affairs. The communities themselves are struggling to retain their language, culture, and identity, and to strengthen the attenuated kinship ties with migrants who were forced to leave, particularly among the younger generation brought up away from their home marae.” The Tribunal concluded, “that Ngati Whatua have been prejudiced by Crown actions and inaction in southern Kaipara and by the Crown’s failure to meet the fiduciary obligations and guarantees of protection of lands and resources made in the Treaty of Waitangi.” [The Kaipara Report, 2006, Waitangi Tribunal, p.321]

The 2013 settlement with the Crown to remedy this unfortunate experience was confined to a package that included an acknowledgement of a well-founded claim, the sale of some Crown land including Woodhill Forest to Ngāti Whātua, some monetary compensation, some culturally significant sites that receive protection and co-management status for Ngāti Whātua, the reinstatement of original place names and some articulated expectation that the Crown and Ngāti Whātua will recognize and respect one another in an altogether different way from this point on. For Ngāti Whātua in southern Kaipara to accept and receive settlement a new governance structure with several operational arms was designed, in which vigorous accountability mechanisms hitherto unexperienced by the five marae have been put in place. The challenge to manage our own tribal estate for the benefit of successive generations is now upon us. Ngāti Whātua has returned to be again a significant economic player in the region.

REFERENCES

Alexander, David, “Consolidation, Development and Public Works Takings”, Report Commissioned by Crown Forestry Rental Trust, January 1999

Goldstone, Paul, “A History of the Woodhill-Helensville Sand Dune Reclamation Scheme and the Woodhill State Forest”, Report Commissioned for the Crown Law Office, January 2001

Small, Fiona, “Twentieth Century Blocks in the Ngati Whatua Southern Kaipara Rohe”, Report Commissioned by Crown Forestry Rental Trust, Wellington, December 1998